With missionary zeal Christians trekked across Europe seeking to convert pagan peoples with vigor in the first centuries of the last millennium. Some Christian missionaries of Europe in efforts to expand the flock, without inciting absorbed peoples, seemed to embrace conversion with syncretic results by selectively incorporating pagan elements. This adaptation of earlier pagan traditions meant a more accessible monotheism for the peoples of Europe. However, the same rich pagan connective tissue of European syncretism became the building blocks for demonization of gods.

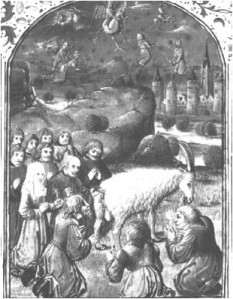

In a letter from Gregory I to Abbott Mellitus, the pontiff recommended the missionary and his brethren adopt a softer approach when converting pagans in England. Gregory believed missionaries like Mellitus should not destroy the pagan temples they encounter but simply remove the pagan gods and sanctify the old space in the name of God. Later in that same letter, Gregory endorses a sacrifice of an oxen as part of a religious feast,” They will sacrifice and eat the animals not any more as an offering to the devil, but for the glory of God to whom, as the giver of all things, they will give thanks for having been satiated…Thus, if they are not deprived of all exterior joys, they will more easily taste the interior ones.” In Gregory’s own words the act of eating and drinking, already ritualized by the church with the concept of the transubstantiation of the Eucharist, was a sure way to win over pagan converts by embracing parts of their ritual feasting traditions.

During the conversion period, Nordic pagan feasts featuring animal sacrifice and ritual drinking designed to honor the gods continued but ultimately took on a decidedly Christian purpose. Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway describes one such instance, “Odin’s toast was to be drunk first- that was for victory and power to the king- then Njordor’s and Freya, for good harvest and peace.” Ritual consumption of libations shifted from pagan to Christian, exemplified by Norwegian Gulaþing laws from the period of King Håkon in the tenth century where Christ and Mary were thanked for abundance and peace instead of Odin and Freya.

If there is a single figure in paganism that so dramatically and liberally linked to the devil during the Middle Ages it is Odin. Tried in Stockholm, Ragvald Odinskarl was accused of robbing four Swedish churches in 1484. Importantly, records claimed that Ragvald Odinskarl had confessed to serving Odin for seven years. Linking the familiar name of Odin to the sacrilegious act of robbing a church was no mistake. Who else would coax man into defiling or thieving from a church, but Satan. It was clear to the cosmopolitan population of Stockholm that Satan worked through the old ways. An example of charm magic connected to the now demonic Odin was a thief finding runestick dating from the late 14th century invoking Odin’s name, as the “greatest among devils.” And throughout the period the chief of the Norse pantheon is known as “the devil Odin.”

Odin as tempter of sin in Christianized 15th century Sweden was furthered by the trial and execution of Erick Clauesson. The servant to a property owner, Clauesson was said to have renounced God and “all his servants” over nine Thursday nights. During those nights Clauesson became a servant of the devil, Odin, in order to gain riches. Convicted of the thefts and burned, Clauesson became a contemporary of Odinskarl in apostasy.

Like the examples of ecclesiastical disbelief in witchcraft, we see the idea of a monolithic approach to conversion of European pagans is far from absolute or unified. Yet when conversion was achieved, the old ways became the ways of Satan and a sure way to spiritual ruin or death.

The following is an excerpt from a personal paper on Witchcraft and Charm Magic. © Copyright site content Asymmetric Creativity/Kevin Cooney (asymmetriccreativity.wordpress.com) 2014-. All rights reserved. Text may not be used without explicit permission.